The Commodification and Infantilization of Femininity

The Kawaii Phenomenon as an Ideological Trojan Horse in China

Introduction: The Cultural Mutation of Kawaii in China

To claim that Japan's Kawaii culture has merely "infected" China would be a disservice to the true nature of this ideological transmission. What we are witnessing is not some passing cultural whim, but rather a calculated, capitalist-driven mutation of gendered ideals that reinforces a specific vision of femininity—one that has been commodified, flattened, and force-fed to the masses. The Kawaii aesthetic, with its saccharine cuteness, pastel tones, and hyper-infantilization of women, has slipped into the pores of Chinese society known as “Meng”, but this infiltration is not benign. It is a product of global capitalist forces that seek to mold the Chinese populace—especially women—into docile, consumptive subjects.

This is not cultural exchange, but cultural expropriation. What the masses experience is not a harmless trend, but the imposition of a pre-packaged, sanitized femininity that serves both domestic and foreign capitalist interests. The effect is double-fold: on one hand, it glorifies a form of femininity that is inherently passive, submissive, and unthreatening, perfectly designed to fit into a capitalist system that profits from the commodification of women's labour, bodies, and desires. On the other, it reinforces patriarchal norms, aligning gender roles with the needs of both international corporate powers and local patriarchal elites who benefit from perpetuating traditional gender hierarchies.

What we see unfolding in China’s urban centres, especially among young women, is a subtle yet powerful ideological shift. This is not a mere aesthetic preference—it is an ideological transformation that shapes behaviours, relationships, and aspirations. Kawaii culture, with its infantilizing features, offers a distinctly neoliberal vision of femininity—one that is packaged, stylized, and ready for consumption. Yet, what is hidden beneath this sugary coating is a deeper, more insidious function: the regulation of women's bodies, minds, and desires in ways that align with capitalistic exploitation. The acceptance of such an aesthetic does not come in isolation—it is integrated into an entire web of societal and economic forces that perpetuate the control over labour, consumption, and identity.

This is the brutal reality behind the cute, the pastel, and the innocent. The commodification of femininity through Kawaii culture in China is an aggressive process of ideological colonization, one that serves to reinforce the material conditions of oppression for women within a global capitalist system. The question is not whether Kawaii is "cute" or "trendy"—the question is how it functions as an ideological tool, serving the interests of colonialists. This is a process of cultural mutation with consequences that need to be interrogated and resisted, not only for what it says about the commodification of gender, but also for what it reveals about the systemic, global structures of power that shape our daily lives.

Why Is Kawaii Culture Popular in China? A Materialist Analysis

To claim that Kawaii culture’s rise in China is simply a matter of innocently adopted aesthetics or harmless cross-cultural admiration is a gross misunderstanding of the material forces at play. The spread of this commodified femininity is neither random nor benign; it is a direct consequence of specific socio-economic conditions, historical power dynamics, and the capitalist imperatives that mold social and gender norms in ways that benefit a few and oppress the many. The increasing visibility of Kawaii culture in China is a complex phenomenon that serves not only to impose a particular, consumable ideal of womanhood but to deepen the structures of exploitation embedded within the global capitalist system. To ignore this material reality is to accept the subtle yet powerful ways that Kawaii aesthetics function as a tool for ideological reproduction.

1. Japanese Cultural Imperialism via Soft Power

It is no accident that Kawaii culture has spread across borders in the way it has. The post-war period saw Japan transform into an economic juggernaut, and with it, the deliberate exportation of a cultural package designed to both mesmerize and control. Through anime, manga, J-pop, and consumer culture, Japan has strategically positioned Kawaii aesthetics as both an economic and ideological force. China, despite the complex political relationship between the two nations, has not been immune to the pull of these cultural exports. However, what is obscured behind the seemingly innocent cuteness of the Kawaii aesthetic is its deeper ideological content. The infantilized, passive femininity it promotes is not just an aesthetic choice but a mechanism of control—reinforcing gender norms that demand women be docile, submissive, and silenced. This is cultural imperialism disguised as entertainment and consumer pleasure, a reality that ensures gender roles remain immobile and exploitable within a capitalist system that profits from such depictions.

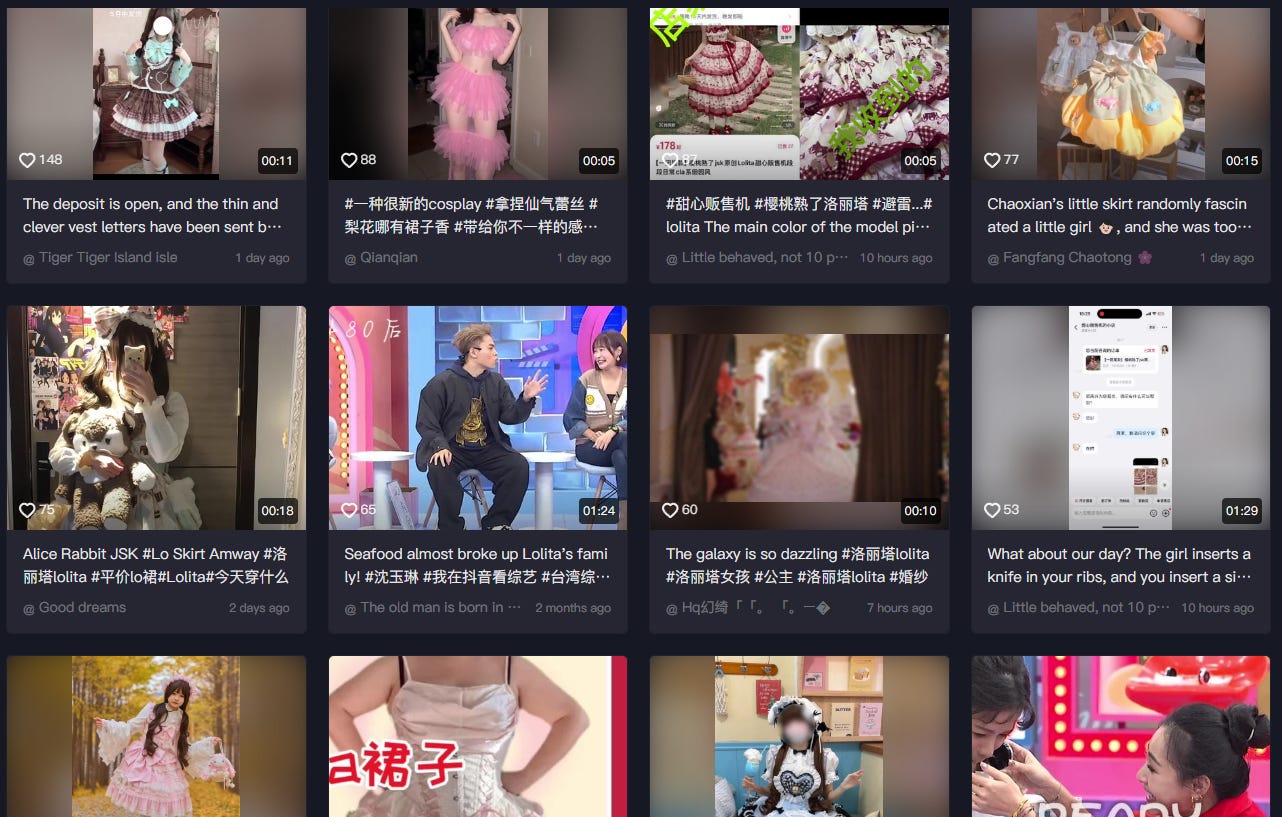

2. Social Media and the Capitalist Appropriation of Femininity

The rise of platforms like Douyin (video), Xiaohongshu, and Taobao (Link) has created a digital environment where Kawaii aesthetics are not just celebrated but are necessary for social mobility and economic success. Far from being a choice freely made by women, the adoption of Kawaii culture on these platforms has become a commodified necessity in a hyper-competitive online economy. Influencers, celebrities, and ordinary women alike are economically forced to embody and perform these infantilized ideals to build their personal brands, attract followers, and generate profit. This commodification of femininity—where cuteness is sold as a product—forces women into a constricting box where their worth is directly tied to their ability to project a marketable image. The digital economy doesn’t just demand women to "act cute"; it demands that they internalize and perform an ideological script that reinforces passive femininity. This, of course, is ideal for the capitalist machine, which profits from the externalization of women’s labour into self-marketing, consumption, and submission (see image below).

3. The Rise of the Live Streaming Economy

The live-streaming boom in China has introduced yet another layer of commodification. Women who wish to succeed in this space must often perform exaggerated, infantilized femininity to gain traction. High-pitched voices, cutesy gestures, and exaggerated expressions of innocence or submission are not simply aesthetic choices—they are economic imperatives. The more a woman conforms to the “Kawaii” ideal, the more she can extract from an audience in terms of attention, validation, and gifts. The live-streaming economy thus reinforces the material reality that Kawaii culture is not merely an aesthetic trend but a structural element of economic survival. The success of Kawaii streamers is evidence that these gendered expectations are not incidental—they are baked into the capitalist framework that drives this industry. In this context, the infantilized portrayal of women is not just a passive consumption of cuteness but an active reinforcement of gendered labour that benefits the patriarchal and capitalist systems.

4. Reinforcement of Traditional Gender Roles under the Guise of Modern Consumerism

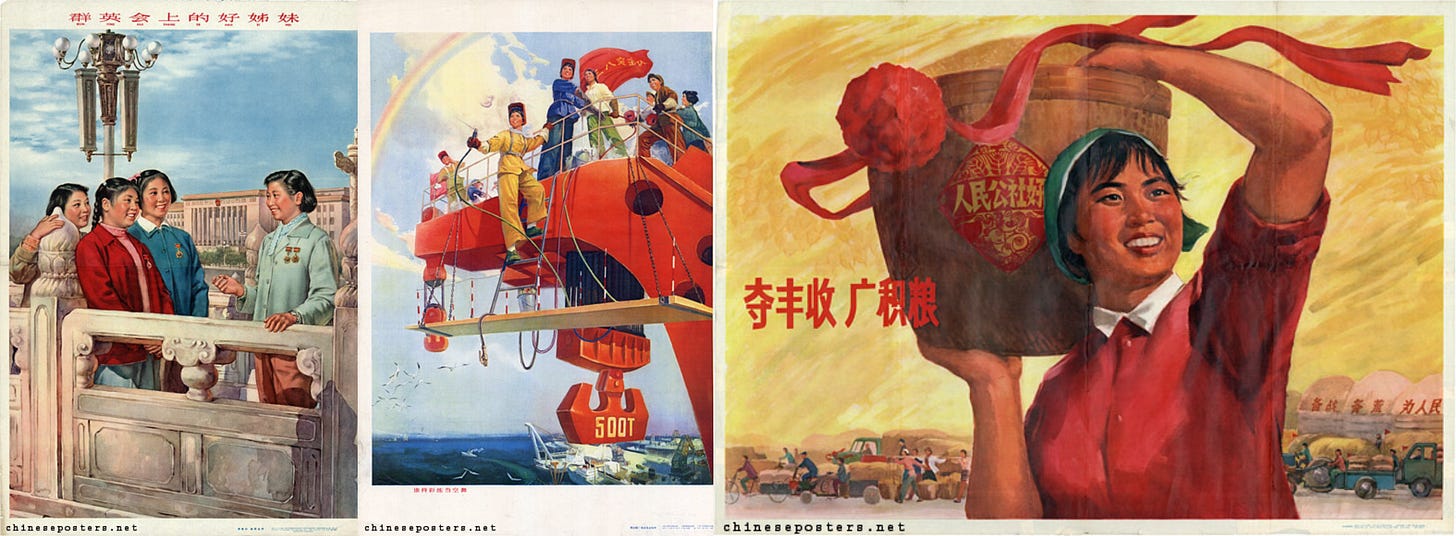

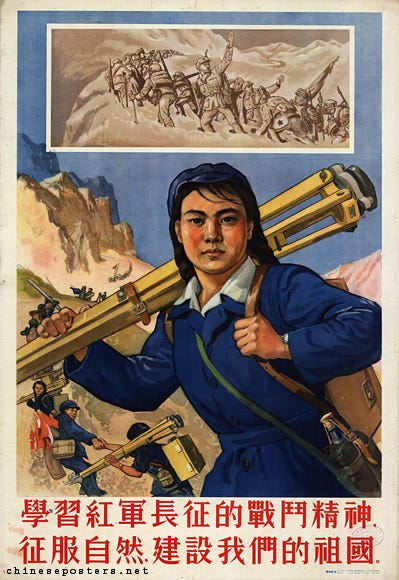

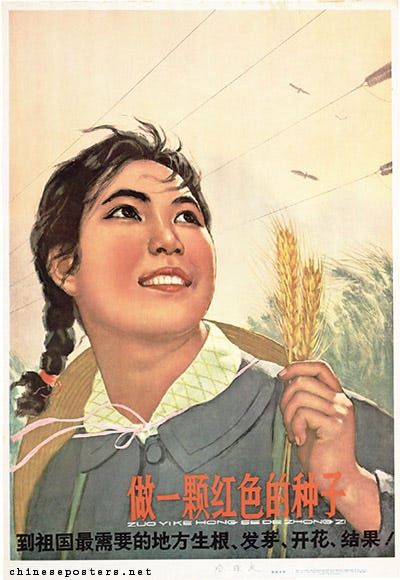

The contradiction at the heart of Kawaii culture’s popularity is that, despite its outward appearance of modernity and global appeal, it subtly reinforces outdated, patriarchal gender norms. The delicate, submissive femininity Kawaii culture promotes is eerily aligned with the reactionary forces that seek to undo the progressive changes Chinese women achieved during the revolutionary period. During this time, women were urged to take part in labour, politics, and social change as active, assertive agents.

Kawaii culture, in stark contrast, diminishes women’s roles to that of fragile, passive beings whose main worth lies in their adorability. Far from a symbol of liberation or empowerment, Kawaii culture reverts gender expectations back to the old patriarchal order. It works as a tool for capitalist forces to maintain a docile, compliant workforce—especially in a digital, post-industrial economy that thrives on the exploitation of gendered labour and performance.

5. Hybridization with Chinese Cultural Elements

The fusion of Kawaii with Chinese aesthetics—such as the emergence of Chinese Lolita fashion and the incorporation of traditional Hanfu into Kawaii-style outfits—serves as yet another example of how foreign ideologies are not merely imported but adapted to serve local capitalist and patriarchal interests. By blending Kawaii culture with elements of Chinese tradition, these hybrid forms appear domestically acceptable while still maintaining the ideological core of gender control and economic exploitation. This blending of cultures masks the original imperialist and capitalist forces at play, making it harder to critique the commodification of femininity when it is presented as something "authentically" Chinese. In truth, these hybrid forms simply serve as another vehicle for the perpetuation of infantilized femininity, which continues to serve the interests of both local and global capitalist systems.

Ultimately, the popularity of Kawaii culture in China is not some innocent cultural exchange; it is the result of deep-seated material conditions that reinforce capitalist and patriarchal power. The “cuteness” of Kawaii is not a trivial matter—it is a weaponized aesthetic, carefully crafted and marketed to make women not just passive consumers, but passive participants in a system designed to exploit them. Whether through the digital economy, live-streaming, or the subtle reinforcement of traditional gender roles, Kawaii culture functions as a material force that shapes women's lives, not as an innocent distraction but as an active agent of ideological control and economic exploitation.

The Problematic Nature of Kawaii Culture and the Infantilization of Women

Kawaii culture is often presented as harmless, even playful—a superficial aesthetic that people can choose to engage with at their leisure. However, when examined through a materialist lens, Kawaii is revealed to be far more insidious than a simple cultural trend. It is not just a set of visual preferences; it is an ideological apparatus that has been meticulously designed to infantilize women, commodify their bodies, and reinforce patriarchal, capitalist structures that depend on women’s submission and objectification. Far from empowering or liberating, Kawaii culture deepens the structures of exploitation and domination that keep women in subordinate roles.

1. Encouraging Childlike Behaviour in Adult Women

The most glaring and troubling aspect of Kawaii culture is the explicit encouragement of childlike behaviour in adult women. Through the adoption of high-pitched voices, wide-eyed expressions, and exaggerated innocence, Kawaii culture conditions women to present themselves as perpetual children, reinforcing the message that women are not meant to mature into fully realized, independent adults. This infantilization is not some innocent aesthetic choice; it is a political tool that seeks to ensure women remain non-threatening, passive, and dependent. When women are expected to embody this infantilized persona, maturity, autonomy, and independence become undesirable traits. The very concept of adult womanhood—capable, assertive, and complex—becomes systematically erased in favour of a picture-perfect, marketable "girlhood" that benefits both capitalist and patriarchal interests. In the process, women’s full potential is stifled, and they are reduced to objects whose worth is primarily found in their cuteness and submissiveness.

2. Overlapping with Problematic Fetishization

Kawaii culture’s aesthetic is not born in isolation; it is deeply entangled with the darker, more disturbing elements of Japan's Lolicon subculture, which has been widely criticized for sexualizing young girls. This overlap raises serious ethical concerns, especially when the same infantilized representations of women start to bleed into mainstream beauty and behavioural standards in China. The blending of innocence and sexuality in Kawaii imagery—a hallmark of Lolicon culture—creates a dangerous and exploitative dynamic, where women's value is reduced to their appearance and demeanour, often with disturbing undertones of sexualization.

The glorification of youth and innocence in Kawaii culture doesn't just celebrate an ideal of femininity; it sexualizes the very idea of childhood, blurring the lines between youthful innocence and adult desires. This entrenchment of sexualized innocence into the cultural fabric feeds into broader systems of objectification and commodification, where women’s bodies are constantly measured against impossible standards of cuteness, purity, and submission. This is not just an aesthetic—it is a deeply problematic, commodified ideology that harms women both socially and psychologically.

3. The Commercialization of Innocence

Under capitalism, even the most intangible qualities—such as innocence and femininity—are transformed into commodities. Kawaii culture is a prime example of this. In a capitalist system, the purity and cuteness that Kawaii represents are not abstract ideals; they are packaged and sold for profit. The beauty industry has long relied on creating impossible standards for women to conform to, selling youth and innocence through makeup, filters, and surgical interventions. Kawaii culture, with its idealized vision of femininity, fits perfectly within this capitalist framework, perpetuating a cycle where women are continually pressured to alter their appearance in order to meet ever-changing beauty standards. From skincare routines to cosmetic surgery, the beauty industry profits immensely by selling the idea that women must be forever young, forever cute, and forever passive. Kawaii culture, in all its infantilized glory, is a cog in this larger machine of consumption—one that turns women’s bodies and identities into marketable products. It serves to deepen women’s exploitation by embedding capitalist consumerism within the very fabric of their self-image.

4. Reinforcing Harmful Gender Norms

Kawaii culture promotes a vision of femininity that is fundamentally passive, decorative, and consumer-oriented. Women who embrace Kawaii aesthetics are encouraged to prioritize their appearance and behaviour over their intellect, talents, and agency. Traits like confidence, assertiveness, and intellectual engagement are not only devalued, but actively discouraged. The message is clear: women should remain soft, sweet, and non-threatening, existing primarily as objects of consumption and decoration for the male gaze.

In this framework, women’s value is intimately tied to their ability to conform to these gendered ideals of cuteness and submission, with little room for deviation. The socialization of women into these passive roles serves to maintain existing power structures by ensuring that women remain docile, dependent, and focused on their appearance, rather than challenging the deeply ingrained patriarchy that perpetuates their oppression.

5. The Benefit to Men at Women’s Expense

Kawaii culture benefits men—specifically, patriarchal structures that derive power and control from the subjugation of women. By constructing an ideal of femininity that is fragile, submissive, and dependent, Kawaii culture reinforces a social order where men hold power and women are relegated to ornamental roles. This serves the patriarchal agenda by reducing women to passive objects whose value lies in their physical appearance and ability to perform docility. Rather than challenging traditional gender roles, Kawaii culture helps to uphold them, ensuring that men remain dominant while women remain subjugated. This infantilization of women not only harms them as individuals but also undermines the collective progress women have made over generations in the fight for gender equality. By turning women into consumable, non-threatening figures, Kawaii culture perpetuates the economic and social structures that keep men in power and women in subordinate, ornamental positions.

Kawaii culture is not merely an aesthetic; it is a systemic tool for the ideological control and commodification of women. It operates within a capitalist and patriarchal framework that seeks to keep women in subjugated roles by infantilizing them, objectifying them, and encouraging a perpetual state of dependence. Far from empowering, it serves to undermine the autonomy and agency of women, reinforcing harmful gender norms and perpetuating the exploitation of their labour and identities. To accept Kawaii culture as anything other than a vehicle for gendered control is to ignore the material conditions that shape and sustain these toxic ideologies.

China’s Potential Pushback Against Kawaii Culture: A Revolutionary Necessity?

The growing penetration of Kawaii culture in China, though often dismissed as a mere trend or aesthetic preference, must be understood in the context of the material conditions and ideological forces that shape Chinese society. While many may view the rise of Kawaii as a superficial import, it is, in fact, a symptom of deeper, capitalist and patriarchal forces at work. Given China’s history of state intervention when cultural trends are perceived to be detrimental to social stability, it is not unreasonable to speculate that the government may eventually take action against Kawaii culture. This would not be out of character, especially considering the government's previous efforts to regulate influencer culture, limit the influence of effeminate male idols, and crack down on excessive cosmetic modifications. In fact, pushing back against Kawaii culture may become not just a reactionary move, but a revolutionary necessity in the struggle to reclaim gender autonomy and resist the forces of commodified femininity.

1. Preservation of Traditional Gender Roles Aligned with Nationalist Goals

One of the primary motivations behind state intervention against Kawaii culture would likely be the desire to preserve traditional gender roles that align with the government's broader nationalist goals. The Chinese state has long promoted a vision of masculinity centred around strength, stoicism, and productivity—qualities that are clearly at odds with the infantilized, submissive femininity embodied by Kawaii culture.

Similarly, the state has elevated the image of the "strong woman" who plays a central role in the nation's economic and social development—one who is not passive or ornamental, but an active participant in labour, politics, and societal progress.

In this context, Kawaii culture’s portrayal of women as fragile, passive, and focused solely on appearance represents a dangerous deviation from these ideals. The government’s push for a more "respectable" model of femininity, one that resists infantilization and objectification, may be a response to this encroaching cultural trend. This pushback would not just be about cultural preservation—it would be a political necessity to ensure that women are not reduced to passive, consumable objects, but remain active contributors to national development, in line with China’s revolutionary past. Kawaii culture, by promoting an idealized but ultimately limiting form of femininity, threatens to undercut these efforts and deepen the existing gender hierarchies that still plague Chinese society.

2. Reduction of Foreign Cultural Influence

Another key motivation behind the potential crackdown on Kawaii culture would be to limit foreign cultural influence, particularly from Japan and the West. As China continues to assert its autonomy and resist external domination, cultural products that originate outside of China are increasingly viewed with suspicion. Kawaii culture, with its origins in Japan and its deep connection to Westernized, globalized consumerism, represents yet another form of ideological colonization that threatens China’s national identity. The government may view Kawaii culture as a foreign import that undermines traditional Chinese values and erodes the revolutionary gains made by women during the socialist period. In that period, women were actively encouraged to participate in the labour force and to contribute to social change as equal, empowered citizens—not as decorative objects of consumption. Kawaii culture’s infantilization of women conflicts with these revolutionary ideals, presenting a vision of femininity that is ultimately at odds with the socialist vision of gender equality. As such, the state may move to label Kawaii culture as a form of ideological imperialism, one that weakens national identity, and the revolutionary values gained from the women’s liberation movement. By confronting this cultural trend, the government could signal its commitment to reclaiming gender roles and promoting a vision of femininity that aligns with the nation's long-standing goals of empowerment and equality.

3. Regulation of Online Behaviour

Kawaii culture’s permeation through social media platforms like Douyin, Xiaohongshu, and Taobao cannot be ignored, as these platforms are central to the digital economy and cultural production in China. If the government perceives Kawaii culture as fostering unhealthy gender roles and mentalities among young women—especially those that prioritize passive, infantilized beauty over intellectual or social engagement—regulatory measures could be introduced to limit its visibility and commercial appeal.

The government has already demonstrated a willingness to regulate online content and behaviour that it deems harmful to public morals, such as cracking down on excessively sexualized content, online influencers who promote unhealthy beauty standards, and "toxic" trends that affect youth mental health. If Kawaii culture is framed as a "toxic" trend, one that encourages unrealistic beauty standards and reinforces regressive gender norms, it could easily fall under the category of content that needs to be curbed for the sake of national social stability. Measures could include censoring Kawaii-related content, imposing stricter regulations on influencers who promote the aesthetic, or even banning certain fashion trends associated with the culture. This could be framed as part of the government’s broader initiative to regulate the digital landscape and protect the mental and physical well-being of young people, particularly young women, who are disproportionately affected by the pressures to conform to these infantilized beauty ideals.

However, any state-led pushback against Kawaii culture must also be understood within a broader context of resistance to capitalist, consumerist forces that seek to exploit women’s bodies and labour for profit. A genuine resistance would require more than just regulatory measures—it would need to be part of a larger, revolutionary push to reclaim autonomy over women’s identities and to combat the commodification of femininity.

To simply suppress Kawaii culture without addressing the root causes—the capitalist exploitation of women’s bodies and the commodification of their labour—would be insufficient and would risk reinforcing state control in ways that are just as limiting and patriarchal. Instead, any revolutionary pushback against Kawaii culture must be linked to a broader struggle for gender equality, economic justice, and the reclamation of culture from capitalist forces that seek to mold women into passive, consumable objects.

In this sense, pushing back against Kawaii culture is not just a cultural or aesthetic struggle—it is a revolutionary necessity, one that requires a comprehensive, materialist approach to gender and society, and a commitment to dismantling the systems of oppression that feed into these toxic cultural trends. The fight against infantilized femininity, whether in the form of Kawaii culture or otherwise, is ultimately a fight against the capitalist and patriarchal systems that depend on such depictions of women to maintain their power. If China’s government chooses to intervene in this cultural trend, it must do so not only for national pride but as part of a larger commitment to liberating women from the gendered constraints imposed by a capitalist world.

The Dialectical Contradiction: Japan’s Soft Power as a Historical Erasure Tool

Kawaii culture is far more than a harmless aesthetic phenomenon or a fleeting cultural trend—it is a calculated ideological construct deeply embedded in Japan’s post-WWII transformation. Following its devastating defeat in the Second World War, Japan embarked on an extensive process of reinvention, rebranding itself not as a nation marred by militarism and imperialist aggression, but as a "cute," pacified society, free from the aggressive, war-driven identity it once held. In the wake of its imperial past, Japan's embrace of softness, innocence, and infantilized aesthetics through Kawaii culture functioned as a strategic attempt to overwrite and obscure the country's violent history. By promoting an image of a harmless, friendly Japan through cultural exports—anime, manga, fashion, and consumer goods—it created a globally palatable image that was detached from the atrocities Japan committed during its imperialist expansion across Asia, including the occupation of China, the Nanking Massacre, and the use of comfort women.

The irony is overwhelming. Chinese consumers, many of whom harbour strong historical grievances and remain deeply critical of Japan’s wartime atrocities, are, at the same time, being enticed to consume a culture that was intentionally designed to erase those very horrors from collective memory. The light-hearted, pastel-coloured imagery of Kawaii is strategically deployed as a weapon of soft power, shaping the way Japan is perceived abroad—especially in neighbouring countries like China. The emotional appeal of Kawaii culture functions as a veneer, glossing over a violent past and distracting from the uncomfortable truths of history. In this way, Kawaii becomes not just an aesthetic, but an instrument of ideological manipulation, an eraser of historical memory, and a tool of cultural diplomacy designed to pacify critical discourse about Japan’s past. By engaging with Kawaii culture, Chinese youth are unwittingly participating in this historical erasure.

The dialectical contradiction here is glaring: in a society where historical memory—particularly the collective memory of the atrocities Japan inflicted on China—remains a powerful force of resistance and national pride, the consumption of Kawaii culture becomes a contradiction in itself. By embracing this "cute" and "harmless" aesthetic without a critical analysis of its origins and political implications, China risks internalizing an ideological framework that undercuts revolutionary consciousness. The emphasis on superficial, commodified cuteness promotes an apolitical, consumer-driven worldview that weakens the collective spirit necessary to confront the deep-seated contradictions of class and gender within Chinese society. Instead of recognizing the history that shaped their present, young people are being pacified, distracted by entertainment and consumer culture that redirects their focus away from meaningful political engagement and historical justice.

This cultural phenomenon, at its core, represents more than just a benign export—it is a Trojan Horse, carefully engineered to infiltrate the consciousness of Chinese society. On the surface, it may seem like an innocuous trend, a harmless diversion, but beneath that facade lies a subtle ideological manipulation that reinforces capitalist consumerism, passive femininity, and historical amnesia. The danger is not just that Kawaii culture becomes a fad, but that it becomes internalized as part of the ideological fabric, diffusing revolutionary sentiment and stifling critical engagement with the pressing issues of historical accountability and social transformation.

By accepting Kawaii culture without questioning its implications, China risks perpetuating a cultural framework that detracts from the nation's revolutionary past and current struggles. Rather than challenging the forces of imperialism and capitalist exploitation, Kawaii culture aligns itself with these very systems, promoting distraction through consumerist pleasure rather than critical engagement with history and material conditions. The state, in its commitment to preserving national identity and revolutionary values, must recognize that the absorption of such an ideology is more than just an aesthetic issue—it is a matter of ideological survival. Allowing the pervasiveness of Kawaii culture without resistance would mean allowing Japan's historical erasure to continue unchecked, while simultaneously pacifying Chinese youth through the hollow comforts of consumerism.

This contradiction is not just an intellectual one—it has real-world consequences. The soft power of Kawaii culture is not benign; it serves the interests of a capitalist system that thrives on consumer distraction and historical amnesia. If China is to reclaim its revolutionary consciousness, it must confront this ideological Trojan Horse head-on, critically analysing the deeper political and historical implications of what is often dismissed as "just a trend." To passively consume Kawaii culture is to inadvertently participate in a broader, global project of erasure—one that seeks to whitewash history, pacify resistance, and reinforce the dominant capitalist and imperialist power structures. This is not a trend to be embraced lightly—it is a battle for historical memory, revolutionary identity, and cultural autonomy. It is a battle that must be waged with critical consciousness and an unwavering commitment to confronting the forces that seek to shape history in their image.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Revolutionary Consciousness from the Kawaii Mirage

The proliferation of Kawaii culture in China is not merely a passing fad or a harmless aesthetic trend—it is a complex, insidious ideological force with profound material implications. At its core, Kawaii culture is a weaponized cultural product, born from Japan’s post-WWII reinvention and deployed as a tool of soft power. Its purpose is to pacify, distract, and reorient, subtly erasing historical memory while promoting a commodified, infantilized femininity that reinforces patriarchal and capitalist systems. As this aesthetic infiltrates Chinese society, particularly through social media platforms and the burgeoning live-streaming economy, it becomes clear that Kawaii is not just an innocuous expression of "cute" fashion—it is an ideological Trojan Horse that undermines revolutionary consciousness, distracts from historical injustices, and weakens the potential for genuine social change.

The danger of Kawaii culture is not simply its prevalence, but its ability to redirect the focus of young people from the contradictions of class, gender, and history to the superficial allure of consumerism. By internalizing an ideological framework rooted in passivity, infantilization, and the commodification of women’s bodies, China risks compromising its revolutionary legacy—one that once empowered women to be active participants in labour, politics, and social transformation. In the process, Kawaii culture serves as a tool of historical erasure, one that obfuscates Japan’s imperial past and distances Chinese youth from the radical consciousness necessary to confront both domestic and global injustices.

Yet, the potential for resistance remains. Confronting Kawaii culture is not just about rejecting an aesthetic—it is about reclaiming control over the ideological forces that shape culture, history, and identity. A revolutionary pushback against Kawaii must involve a deeper, materialist critique of the capitalist systems that promote such commodified, gendered ideals, and a return to the emancipatory spirit of China’s socialist past—one that fought for the liberation and empowerment of women, not their subjugation through consumerist fantasies. In this context, reclaiming revolutionary consciousness becomes a vital task—not only for preserving historical memory but for creating a future where women’s identities are no longer shaped by the infantilizing demands of a capitalist world but by their own autonomy and political agency.

Ultimately, the challenge lies not just in the superficial aesthetics of Kawaii culture, but in the deeper ideological work required to dismantle the patriarchal, capitalist structures that perpetuate it. China’s revolutionary struggle must move beyond mere resistance to cultural imports—it must embrace a transformative critique of the forces that commodify and exploit women’s bodies, histories, and identities. Only by confronting the contradictions embedded within Kawaii culture—and the ideological apparatus that supports it—can China ensure that the fight for gender equality, social justice, and historical accountability remains at the forefront of its national consciousness.

Kawaii culture, then, is not just a cultural import—it is an ideological battlefield, one that demands a revolutionary approach rooted in materialist analysis, historical awareness, and an uncompromising commitment to emancipation. Only by rejecting the passive, infantilized femininity it promotes can we build a future where women are free to define themselves on their own terms, unshackled from the constraints of both foreign cultural domination and domestic patriarchal exploitation.

References

Lostak, M. (n.d.). Soft power in a globalized world: The case of Japan. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/%40martin.lostak/soft-power-in-a-globalized-world-the-case-of-japan-e00d40c10531

Neon Tommy. (2013, October). East Asian kawaii culture: Insidiously anti-woman? Retrieved from https://www.neontommy.com/news/2013/10/east-asian-kawaii-culture-insidiously-anti-woman.html

Pacific Ties. (n.d.). The Kawaii invasion: Japan flexing more soft power in America? Retrieved from https://pacificties.org/the-kawaii-invasion-japan-flexing-more-soft-power-in-america/

Rijag. (n.d.). Kawaii culture and soft power. Retrieved from https://rijag.org/en/kawaii-culture-and-soft-power/

Rijag. (n.d.). Kawaii culture and soft power: Part II. Retrieved from https://rijag.org/en/kawaii-culture-and-soft-power-part-ii/

ScholarsBank, University of Oregon. (n.d.). [Article on kawaii culture]. Retrieved from https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/items/583788d8-bbc8-4475-b1ed-031b695f3373

Scholar Commons, University of South Carolina. (n.d.). [Research article on kawaii culture]. Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=uscusrj

The China Journal. (2016, April 21). Pretty innocent? Asian girls and the cult of cuteness in Asia. Retrieved from https://china-journal.org/2016/04/21/pretty-innocent-asian-girls-cult-of-cuteness-asia/

University of Washington. (n.d.). Soft power through the lens of Japanese materialism and knowledge production. Retrieved from https://uw.manifoldapp.org/read/soft-power-through-the-lens-of-japanese-materialism-and-knowledge-production/section/33380729-2e36-423e-bd49-daf09ecdb109

YouTube. (2023). [Video on kawaii culture and soft power]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IM2VIKfaY0Y

Asia Media, Loyola Marymount University. (2021, October 4). Japan: Does kawaii culture infantilize women? Retrieved from https://asiamedia.lmu.edu/2021/10/04/japan-does-kawaii-culture-infantilize-women/

Dilton, R. (2019). Human trafficking. New York State Bar Association. Retrieved from https://nysba.org/NYSBA/Sections/International/Seasonal%20Meetings/Tokyo%202019/Coursebook/Dilton%20Ribeiro%20-%20Human%20Trafficking.pdf

Gab China. (n.d.). Chinese social media. Retrieved from https://gab-china.com/chinese-social-media/

Image & Narrative. (n.d.). [Academic article on kawaii culture]. Retrieved from https://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/view/127

Jing Daily. (n.d.). Gamer girl culture in China: Gen Z and TikTok trends. Retrieved from https://jingdaily.com/posts/gamer-girl-china-gen-z-tiktok

Kirj. (2023). [Academic article on kawaii culture]. Retrieved from https://kirj.ee/wp-content/plugins/kirj/pub/TRAMES-3-2023-311-324_20230821152905.pdf

MDPI. (2018). Arts, 7(3), 24. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/7/3/24

The Hanfu Story. (n.d.). Lolita dresses: Hanfu Lolita and Chinese Lolita fashion. Retrieved from https://thehanfustory.com/collections/lolita-dresses-hanfu-lolita-chinese-lolita

UCLA Center for the Study of Women. (2017, July 21). Being kawaii in Japan. Retrieved from https://csw.ucla.edu/2017/07/21/being-kawaii-in-japan/

Vantage Digital. (n.d.). The rise of the cute economy in China: A comprehensive look. Retrieved from https://vantagedigital.com.au/the-rise-of-the-cute-economy-in-china-a-comprehensive-look/

Auckland War Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Cultures, languages, and linguistics. Retrieved from https://www.awa.auckland.ac.nz/index.php?p=cultures-languages-linguistics&textid=1120

China Perspectives. (2024). Navigating the economy of ambivalent intimacy: Gender and relational labour in China’s livestreaming industry. Retrieved from https://pure.eur.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/61561693/Navigating_the_economy_of_ambivalent_intimacy_gender_and_relational_labour_in_China_s_livestreaming_industry.pdf

FHSU Scholars Repository. (n.d.). [Cute politics!: articulating the kawaii aesthetic, fandom and political participation]. Retrieved from https://scholars.fhsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=comm_facpub

Krijnen, T., & Ye, X. (2024). Being pretty does not help your success: Self-representation and aspiration of China’s female showroom hosts. Erasmus University Rotterdam. Retrieved from https://pure.eur.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/135611856/ye-krijnen-2024-being-pretty-does-not-help-your-success-self-representation-and-aspiration-of-china-s-female-showroom.pdf

Mancunion. (2016, March 2). Kawaii culture: The psychology of sweetness. Retrieved from https://mancunion.com/2016/03/02/kawaii-culture-the-psychology-of-sweetness/

ResearchGate. (2023). Making Nüzhibo: Commodified intimacy and gendered labour in Chinese live-life streaming. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378332157_Making_Nuzhubo_Commodified_Intimacy_and_Gendered_Labour_in_Chinese_LiveLife_Streaming

SAGE Journals. (2024). [Academic article on gender and media]. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20594364241230436?icid=int.sj-abstract.citing-articles.2

SciELO Brazil. (n.d.). [Research article on kawaii culture and gender]. Retrieved from https://www.scielo.br/j/cpa/a/Yvrx8GfcZ7rYXkd3vznKV5h/?format=pdf&lang=en

Shift London. (n.d.). When cute turns toxic: The dark side of kawaii culture. Retrieved from https://www.shiftlondon.org/features/when-cute-turns-toxic-the-dark-side-of-kawaii-culture/

Technology Review. (2022, July 4). How China controls how livestreamers act and dress. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/07/04/1055349/china-controls-livestreamers-act-dress/

Wiscomp. (n.d.). The pretensions of kawaii: Schoolgirls and cute sexism. Retrieved from https://logingender.wiscomp.org/the-pretensions-of-kawaii-schoolgirls-and-cute-sexism/

NBC News. (2021, February 8). China proposes teaching masculinity to boys as state is alarmed by changing gender roles. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/china-proposes-teaching-masculinity-boys-state-alarmed-changing-gender-roles-n1258939

Nikkei Asia. (n.d.). Kawaii culture hurts Japanese women in business. Retrieved from https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Kawaii-culture-hurts-Japanese-women-in-business

Northeastern University. (2022, January 26). China’s new regulations on men’s appearance on TV. Retrieved from https://news.northeastern.edu/2022/01/26/regulating-mens-appearance-on-tv/

Ottawa University Repository. (n.d.). [Academic research on gender and culture]. Retrieved from https://ruor.uottawa.ca/items/cbd21295-e1e2-4180-b3c8-a8d98117ccc9

Psychology Today. (2007, March). Global psyche: One nation under cute. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/articles/200703/global-psyche-one-nation-under-cute

PubMed Central. (n.d.). [Research article on gender studies and culture]. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9268205/

South China Morning Post. (2021, September 9). China’s crackdown on the entertainment industry and its targeting of celebrities. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/yp/discover/news/asia/article/3148352/hot-topics-chinas-crackdown-entertainment-industry-targeting

Toronto Scholars Portal. (n.d.). [Academic research on gender and cultural studies]. Retrieved from https://utoronto.scholaris.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/39e66a9a-0ddf-41c6-921b-1d779c7e4616/content

Vox. (2022, October 17). China vs. fandom: Danmei, censorship, and Qinglang social media regulations. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/culture/23404571/china-vs-fandom-danmei-censorship-qinglang-social-media

YouTube. (2023). China’s Pop-Culture Crackdown Widens After It Hits Its Biggest Movie Star | WSJ. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PEmcNd9yArU&t

Academia.edu. (n.d.). Cool Japan and the commodification of cute: Selling Japanese national identity and international image (by Brian Lewis). Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/10476256/_Cool_Japan_and_the_Commodification_of_Cute_Selling_Japanese_National_Identity_and_International_Image_by_Brian_Lewis

Academia.edu. (n.d.). Just looking: Tantalization, lolicon, and virtual girls. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/26345998/Just_Looking_Tantalization_Lolicon_and_Virtual_Girls

Economist. (1999, May 6). The darker side of cuteness. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/asia/1999/05/06/the-darker-side-of-cuteness

Image & Narrative. (n.d.). [Research article on kawaii culture and media]. Retrieved from https://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/view/127

METU Open Repository. (n.d.). Examination of sexualized depictions of young schoolgirls in anime: Opinions and perspectives of Japanese women. Retrieved from https://open.metu.edu.tr/bitstream/handle/11511/105628/Examination%20of%20Sexualized%20Depictions%20of%20Young%20Schoolgirls%20in%20Anime%20Opinions%20and%20Perspectives%20of%20Japanese%20Women%20(1).pdf

Millennial Anime Fan. (2018, January 26). What is a lolicon? Understanding the controversial part of otaku culture. Retrieved from https://millennialanimefan.wordpress.com/2018/01/26/what-is-a-lolicon-understanding-the-controversial-part-of-otaku-culture/

Spectator. (n.d.). The dark side of cute culture. Retrieved from [https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-dark-side-of-cute-culture/](https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-dark-side-of-cute

VICE. (n.d.). Manga, abuse, and children: Japan’s controversial relationship with sexualized depictions in media. Retrieved from https://www.vice.com/en/article/manga-abuse-children-japan-sexual/

VICE. (n.d.). Japan’s child pornography problem: The debate over manga and anime depictions. Retrieved from https://www.vice.com/en/article/japan-child-pornography-manga-anime/